Review of Crimson Peak.

Guillermo del Toro’s ode to Gothic literature begins with one of those typically useless warnings: “Beware Crimson Peak!” Not something actionable like, “Don’t trust Thomas Sharpe and his sister” or “Stay away from Allerdale Hall if you value your life.” No: “Beware Crimson Peak,” delivered to a terrified little girl by her dead mother’s frightful apparition. The warning isn’t without purpose. It’s a lazy trick to set an ominous mood for audiences – without ending the story before it begins. After all, a practical warning would mean that the film’s plucky heroine, Edith Cushing (Mia Wasikowska), never would marry Sir Thomas Sharpe (Tom Hiddleston) and never go to Allerdale Hall to experience the horror, the horror!

If this sort of atmospheric but pointlessly cryptic warning were the film’s only instance of crystal ball-gazing, it would hardly be worth mentioning. But Del Toro’s curious over-direction consistently saps the film’s suspense by anticipating the story and placing us too far ahead of the narrative to ever be surprised. A teacup’s significance, for instance, is easy to figure out on account of Del Toro repeatedly drawing our attention to it. Jessica Chastain’s performance is delicious and unnervingly creepy, but also never leaves any doubt as to her character’s eventual malevolent role in the plot. Even in the art production we find a saturation of predictive details, enough to make the film a victim as much as beneficiary of Del Toro’s meticulous attention. The details are laden with such fixed symbolism that they become literal and pedantic. In Buffalo, Edith’s home with her father is luxurious, yes, but more importantly, traditional and safe; a symbol of familial love. Allerdale Hall, the titular Crimson Peak, is a beautiful distillation of the Gothic household, a many-fold amplification of a House of Usher or any other decrepit Victorian haunt. Consequently it is the architectural embodiment of the Sharpe siblings’ family history, tragedy and horror. Of course bad things will happen here, because it looks precisely like the sort of place in which bad things happen. (Plus, we’ve been warned.)

Crimson Peak is unquestionably beautiful, however, thanks to Del Toro and production designer Thomas E. Sanders; a lushly macabre psycho-physical fantasia of architectural ruin, moral decay, and doom that alone is worth the price of admission. Built as an actual physical set, Allerdale Hall bursts with antiquity and a faded opulence rooted in the conviction that no amount of ornamentation is excessive. A hole in the roof allows leaves, and later snow, to fall in, as if the building itself was being reclaimed by the elements, which it is: Built atop a mass of vibrant red clay, the house’s walls and floors dramatically ooze the stuff as a sign of its condemnation to an eventual drowning death.

It is an arthouse setting in need of an elliptical arthouse narrative to counteract its literal-mindedness. Where over-direction diffuses tension in the narrative, the production’s over-design contributes to the impression that we are experiencing a theme park ride – a Disney’s Haunted Mansion writ large and stripped of camp. Several occurrences – a moving shadow here, a ghostly effect there – occur in the background, beyond the characters’ awareness, demonstrating a tendency to stage for the audience rather than create a symbiosis between character and setting. Of the overt effects – the ghosts Edith encounters throughout her ordeal – they, too, are well-designed, all sinewy and tortured. But the criticism leveled against the fantastical 1999 film adaptation of Shirley Jackson’s The Haunting of Hill House applies here just as well: the special effects call attention to themselves as special effects. Having already grounded the apparitions as matters of fact in a scene that resorts to the old trope of ghosts as emotionally-charged impressions on places, Del Toro’s full spectral Monty further demonstrates how his homage to the Gothic latched onto its sensationalist rather than subtle forms. In this sense, the larger problem stems from the unfortunate turn the Gothic took, as a genre, towards horror rather than the terror of novels by genre pioneers like Ann Radcliffe and Del Toro’s literary crushes, the Bronte Sisters. As Radcliffe pointed out in her essay On the Supernatural in Poetry, “Terror and horror are so far opposite, that the first expands the soul and awakens the faculties to a high degree of life; the other contracts, freezes, and nearly annihilates them….and where lies the great difference between horror and terror, but in the uncertainty and obscurity, that accompany the first, respecting the dreaded evil?” Without any ambiguity in either the characters, the settings, or the supernatural elements – the essential element to inspire terror and nurture a feeling of dread and impending doom – what remains is the blunt force of style.

It doesn’t help to accede to Del Toro’s insistence that the film is a Gothic romance moreso than a horror story because while there is a love story of sorts at the heart of the film, it never actually feels romantic. Edith and Thomas never are on the same page, as it were; when Edith loves Thomas, he’s in love with her money. By the time he does love her, she’s discovered the horrible truth about him and readies her escape. Romance presupposes a narrative in which two lovers must strive to overcome obstacles to finally come together. What we get might deserve its own word: romantish.

The film isn’t helped by a meta-fictional gesture performed with success in Grand Budapest Hotel: nested narratives. In Wes Anderson’s hands, the narrative layers involved a young girl reading a memoir about an author’s younger days in which he learned the poignant story of the Grand Budapest Hotel’s owner (the crux of the film). The device worked as a commentary on memory, nostalgia, and the way in which past and present interact. In Crimson Peak, the film is presented as a novel written by Edith, featuring herself as a protagonist who, in addition to enduring Gothic tribulations, also is an author aspiring to write a novel. The contrivance creates a distance, a numbing effect that sabotages the potential for an emotional engagement with the characters. Worse, however, is that the decision to veer into a quasi-postmodern format comes with the only example in recent memory of a film that explains the function and meaning of its own constituent parts as it unfolds. Hence, we are told that ghosts are metaphors for the past and the story isn’t a ghost story but, rather, a story with ghosts in it – readings that are entirely consistent with the film and also entirely superfluous. Once again, we’re confronted with the film’s utter lack of ambiguity and, consequently, of mystery.

When Del Toro released Pacific Rim, the end result was a source of pure grinning giddiness even though the characters and story were cobbled together from Hollywood cardboard. The difference from Crimson Peak is that the genre to which he turned his considerable imagination towards – the giant robot and monster genre – depends far less on narrative than on large-scale action. Style is substance, and that worked wonderfully well for a memorably epic battle to save the planet from invasion. Crimson Peak’s native genre isn’t nearly as forgiving.

Yet it would be an exaggeration to judge the film as bad. For all its shortcomings, its narrative does respect an internal logic. While the characters owe more to the strength of the cast’s performances than to depth of writing, there is enough to appreciate the struggles of a smart heroine in the face of a monstrous deception, a villain who experiences a change of heart, and a magnificently unhinged Jessica Chastain as the film’s mortal threat. And despite the film’s marketing as a horror film, Del Toro’s deviation from the horror genre makes it a film for people (like me) who don’t typically enjoy horror. There is violence, yes, and it is brutally effective, but Del Toro is no butcher. The violence, though gory, is surgical and respectful; there’s none of the tawdry wallowing in the victims’ pain in which horror filmmakers indulge. Ultimately, it is the beautiful vision the film presents that justifies the price of admission. Crimson Peak may lack soul but, in the end, it is spirited.

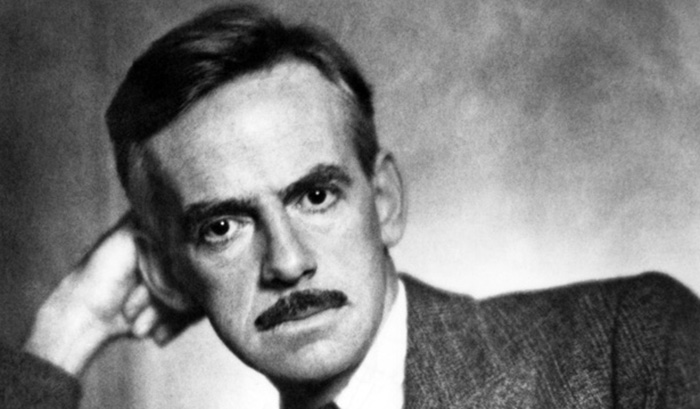

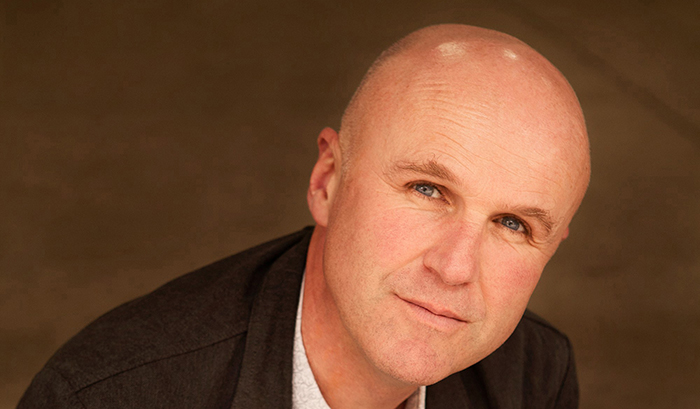

Frédérik is the Page’s Assistant Editor and Resident Art Critic. He can be reached via eMail at fsisa@thefrontpageonline.com or through various social media via www.kimtag.com/writer