Review of Black Panthers for Beginners and Civil Rights for Beginners.

When it comes to race, any discussion I might have necessarily begins with this admission: As a white man, I don’t know what it’s like to be black in America. If you are white, dear reader, then guess what? Neither do you. This doesn’t mean we can’t understand or relate, but it does mean that we shouldn’t assume that our personal experience is universal.

When it comes to race, any discussion I might have necessarily begins with this admission: As a white man, I don’t know what it’s like to be black in America. If you are white, dear reader, then guess what? Neither do you. This doesn’t mean we can’t understand or relate, but it does mean that we shouldn’t assume that our personal experience is universal.

While there is no denying the progress that America has made in first abolishing slavery and then moving towards dismantling segregation, the issue of race isn’t strictly a legal one. It’s also cultural, personal and ultimately political. Remember that even the supposedly enlightened North opposed slavery during the Civil War, but was very much racist when it came to interactions between blacks and whites. No chains or whips for you, Mr. Black Man, hooray! Just stay away from my daughter, don’t move into my neighbourhood, and stop eyeballing the silverware.

Part of the problem is semantic. The word “racism,” like most words in politics, has a fluid definition veering from theories of identity politics to the realities of violent oppression. To conservative pundits, racism is limited to slavery, beatings, lynchings, separate entrances, and so on, which is why being labelled a racist provokes such howls of outrage. By their reasoning, if they’re not dressed in white sheets and roasting marshmallows on burning crosses, they’re not racist – and charges of racism become racist in and of themselves.

Implicit Bias

Yet however much of the national conversation on race hinges on different perspectives on what constitutes racism. Racial prejudice is a definite, scientifically observable phenomena. Efforts such as Harvard Universities Project Implicit reveal that whatever our conscious thinking may be, we nevertheless harbor unconscious biases that can influence us without our awareness. As the Kirwan Institute for the Study of Race and Ethnicity summarizes:

- Implicit biases are pervasive. Everyone possesses them, even people with avowed commitments to impartiality such as judges.

- The implicit associations we hold do not necessarily align with our declared beliefs or even reflect stances we would explicitly endorse.

- We generally tend to hold implicit biases that favor our own ingroup, though research has shown that we can still hold implicit biases against our ingroup.

Racism today remains the pervasive institutionalization of implicit bias, a prejudice that continues to favor whites at the expense of blacks and other ethnicities. It is a key factor underlying disparities in racial profiling, redlining, voting disenfranchisement, criminal sentencing. But discussing it, especially in the practical day-to-day experience of black Americans, is a problem when right-wing commentators deny that there’s a problem in the first place. This, of course, is the tighty-righty conservabots’ modus operandi, whose rants against diversity, as both a fact of life and a worthy value, emphasize their implicit preference for homogeneity and conformity – by white American standards, of course. Follow Roy Edroso’s Rightblogger column at Variety and read for yourself. Or witness how the Republican party’s presidential primaries fuel the worst impulses in American culture.

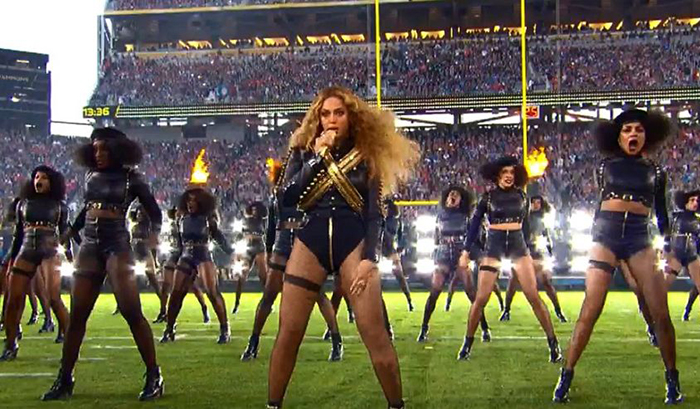

The problem is much more serious than agreeing on the existence and manifestation of racial injustice. The way in which black people talk about their experience is also subject to policing both literally and figuratively. On a broad level, conservabots are already very quick to denounce any expression of anger that isn’t related to gay marriage, climate change, or the only victims of injustice they recognize: themselves. (Anger is a fault in liberals, but entirely proper for conservatives, apparently.) By delegitimizing anger as an understandable response to injustice or harm – such as the senseless deaths of black people like Erik Garner and Sandra Bland – conservative white America imposes its own narrative on the black American experience. The “controversy” over Beyonce’s performance of Formation at the Super Bowl is a recent example. Objecting to visual references to the Black Panthers and #blacklivesmatter, some police unions discussed a boycott of Beyonce’s world tour. Ed, a political science professor who blogs at Ginandtacos.com, disassembles the affair quite nicely but the point is this: Black people are not meaningfully free to air grievances except through what whites deem to be politically-acceptable channels – with proper deference, naturally. (We see how well that worked for black victims of police violence in Chicago. Besides, the police unions’ thin-skin misses the point that black mistrust of police isn’t a new phenomenon, but reaches back in history, before the Black Panthers even emerged. It also ignores the fact that there are serious systemic issues with policing in America beyond militarization.).

For Beginners Books Educate

Any informed discussion must involve education. Two For Beginners books, released in 2015, bang us right out of the gate.

Any informed discussion must involve education. Two For Beginners books, released in 2015, bang us right out of the gate.

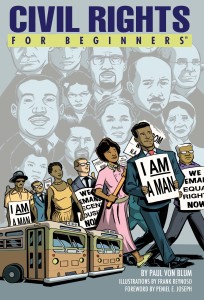

The first, Civil Rights for Beginners by Paul Von Blum (with illustrations by Frank Reynoso)– a senior lecturer on African-American Studies at UCLA – is a concise but thorough overview of the civil rights movement from slavery and Jim Crow to the Black Panthers and current intersectional civil rights efforts. It goes beyond the best-known watershed moments to chart a long history of struggle by brave, defiant, controversial, radical, inspiring and utterly fascinating people and organizations. What emerges from this simultaneously thoughtful and moving history is the perspective that the civil rights movement isn’t reducible to a discrete set of victories or defeats, but comprises a continuum of thought and activism that lives on today. Nor is the movement reducible to emancipation from slavery and segregation. It spans a wide range of economic and political agitations as relevant today as they were in the recent past.

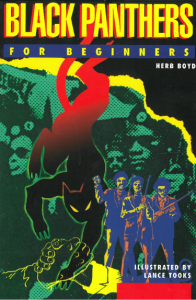

Second is journalist and teacher Herb Boyd’s Black Panthers for Beginners (illustrated by Lance Tooks), a crackling read that serves as an excellent companion to Von Blum’s book. It tells the story of the Black Panther Party for Self-Defense from its founding on Oct. 15, 1966 by Huey Newton and Bobby Seale to its gradual disintegration during the 1980s. The portrait that emerges is one that resists easy judgements. Boyd is as unflinching in acknowledging the Panthers’ strife, both internal and external, as he is in praising their heroic aspects – their Free Breakfast for School Children Program, for instance, which collected food donations from local merchants and distributed meals to hungry children. For all the controversy their militancy generated, at times for entirely justifiable reasons, the Black Panthers presented an opportunity to challenge the fundamental narrative imposed on black communities by white America. If anything, whether it’s the Black Lives Matter movement or Beyonce’s visual invocation of the Panthers, the backlash is a stark revelation of white insecurity.

Not Enough

But is education enough? Is it possible to counteract a mindset that disenfranchises blacks, that condones the appropriation of Native American cultures as branding and mascots, that denies women agency over their own bodies, that insists on tarring all Muslims as terrorists? These attitudes are all related in a core xenophobia often masked by seemingly genteel rhetoric. In relating a deplorable incident at CSU LA, Breitbart.com described a speech by Ben Shapiro in which “he explained that there are three kinds of diversity: Diversity of color, diversity of values, and diversity of ideas. Only the last kind, he said, was valuable to society and could create stable and healthy communities.”

But this is precisely the sort of naïve, whitewashing misdirection that mars genuine progress in race relations. Once again: Dismissing diversity of color and values, in reality as well as in theory, is convenient when your color is white and your values are reactionary. Another commentator, however, offers a more reasonable perspective along with a sober assessment of the value of politics:

“We live in a big, diverse society…Politics is an activity in which you recognize the simultaneous existence of different groups, interests and opinions. You try to find some way to balance or reconcile or compromise those interests, or at least a majority of them. You follow a set of rules, enshrined in a constitution or in custom, to help you reach these compromises in a way everybody considers legitimate.”

That commentator? Not some flamboyant liberal but rather The New York Times’ own cozy conservative, David Brooks, who remains one of the Right’s few civil and thoughtful voices. His observations regarding anti-politics are entirely on-point. The great tragedy of our era is that the diversity-averse American body politic no longer has a shared framework in which to discuss and resolve ongoing social challenges like racism.

Books alone aren’t enough to bridge the deep divides, of course. But with fascinating quality primers like Black Panthers for Beginners and Civil Rights for Beginners, there’s no reason to be ignorant of history, black Americans’ experience, and the brave efforts to overcome our divisions.

Review copies of Black Panthers for Beginners and Civil Rights for Beginners provided by For Beginners Books.

Visit www.forbeginnersbooks.com for more information.

Frédérik Sisa is the Page’s Assistant Editor and Resident Art Critic. He can be reached via eMail at fsisa@thefrontpageonline.com, and via social media through Twitter, Instagram, and GoodReads.