Fifty-seven years ago tomorrow night, just after 8 o’clock Eastern time, there was a terrible albeit understandable, miscarriage of American justice:

For the alleged, but never close to proven, crime of passing atomic secrets to the Soviet Union, Julius Rosenberg, 35 years old, and his wife Ethel, 37 years old, parents of two young boys, were executed at Sing-Sing Prison. The New York D.A. may as well have charged them with riding horses across the Atlantic.

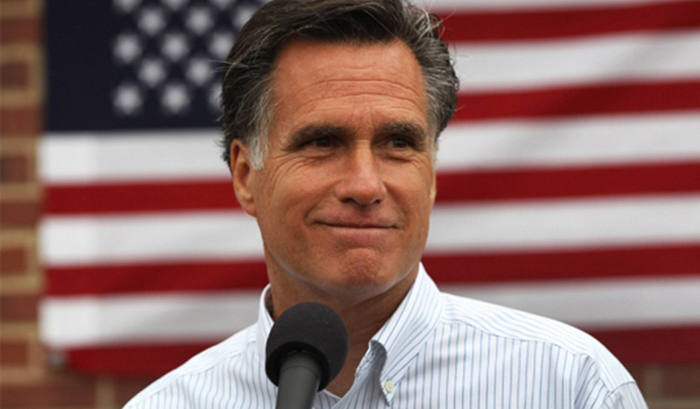

[img]888|left|Julius and Ethel Rosenberg||no_popup[/img]Friday, June 19, 1953, deserves to live in infamy as much as Dec. 7, 1941 because the crime was more grave than the Japanese attack — we deliberately, and relentlessly, killed two of our own.

They spent the last three years of their lives staring hopelessly through prison bars, two rather dreary shlubs who had led very brief, pointedly colorless, decidedly unfulfilling lives.

They were not fighters. They were heads-down people who reflected their times. Born three years apart during World War I, they grew up in loveless, funless homes, in families who accepted cold-water flats as their deserved lot in life.

[img]889|left|Julius and Ethel Rosenberg||no_popup[/img]Relatively Loyal?

Their families — especially Ethel’s — had never been fond of them in regular times. Once arrested, they were dead meat. Vicious, conspiring relatives worked heartlessly against them before and after they had been arrested.

Ethel and Julius matured in the bitter teeth of the Great Depression — far more grim today’s relatively prosperous depression environment.

They did what thousands of young people did in the 1930s, joining the Communist Party, openly, proudly, not at all covertly.

Politically and socially, the war years in the 1940s were at least palatable for young Communists when the Soviet Union was our major ally.

After the war, the warmth between Washington and Moscow became chillier and then froze, triggering the launching of an unprecedented witchhunt that continued apace for a decade remembered as one of the ugliest in American annals.

The tone was largely established by the crossdressing idiot who ran the FBI and the White House — yes, every President — from the 1920s through the ‘60s, J. Edgar Hoover, the cover boy for the magazine “Fools Illustrated.”

“Red Scare” was on millions of lips. Friends squealed on friends, and overnight they became deadly enemies instead of merely former pals. The sickminded roly-poly J. Edgar would dash home, secretly don one of his favorite taffeta dresses, and cavort around his off-limits home, gleefully celebrating the number of pathetic Communist pigeons’ lives he had ruined that day.

Communist Party membership went from socially acceptable to oops, there goes my livelihood, my family and then my life.

As early as 1946, less than a year after the war ended, crazy but widely feared J. Edgar was telling reporters:

“Red Fascism has become a major force in unions, newspapers, magazines, book publishing, radio, movies, churches, schools, colleges, fraternal orders, and the government itself.”

J. Edgar’s mantra was, “a Red beneath every bed,” and if yours was missing, the government eagerly would supply one.

They Were Created for History

The Rosenbergs are a meticulously perpetrated American tragedy, possibly without historic parallel.

A couple of New York Jews who were the antithesis of the normal brash image the phrase connotes, the Rosenbergs were railroaded as shamelessly, as openly, as routinely, as guilelessly as poor blacks were being tortured and slaughtered in those days in the Deep South.

Their calculated killings were one of the most spectacular miscarriages of justice in our generally admirable legal history. In the jargon of the day, they were railroaded, irreversibly determined to be guilty before entering the first courtroom.

Even though they were committed Communists, I believe they were as guilt free as anyone reading this essay.

From a separate perspective, the crime of killing the Rosenbergs was understandable because the prevailing hysterical atmosphere of the time monsterishly drove the case, from their carefully staged arrests until the final stubborn breath was electrically drained from Ethel, the tougher to kill.

To look at Julius and Ethel, if you did not know anything about them, you would insist they were pigeons, a couple of shlemiels shipped across the country from Central Casting.

When they were arrested, weeks apart, in the summer of 1950, the Soviet-like McCarthy Era was in its infancy. Julius and Ethel fitted the desired profile of shlemiel Reds. It was not only acceptable but desirable to publicly throw darts at these dastardly Jews, and New York Jews at that.

(In the non-Jewish world, a shlemiel would resemble the Poor Soul character the late comedian Jackie Gleason made famous on television in the 1950s and ‘60s.)

Ubiquitously by the end of the 1940s, steaming pressure was building on legal authorities to cleanse covert nests of Communist spies before they destroyed America, as they surely would.

The New York District Attorney’s office needed a sensational knockoff, a trophy case, to show Washington and the rest of worried America that they were successfully fighting the dreaded enemy within.

Julius and Ethel, born to pigeonhood, laid in unsuspecting wait.

Their case was cooked so outrageously mischievously that it must have been devised by one of those fat Southern sheriffs who used to kill black kids for a living and then boasted about it.

Enter Julius and Ethel Rosenberg — who were so astonishingly tailored for their tragic roles, they could have reminded you of baggy pants comedians who, supposedly unintentionally, wandered onto vaudeville stages a hundred years ago.

Abandoned in their last three years by virtually everyone they had known in regular times, they were as alone as if they had been orphaned at birth and immediately contracted lifetime deadly contagious diseases.

I mourn their 50 years’ early demise, but the despicable prosecutor and the even worse judge went to their graves smilingly clutching their Rosenberg trophies.

June 19, 1953, shall ever remain a day of infamy, even if greatly muted because few remember and fewer mourn.