[img]7|left|||no_popup[/img]There is a scene in which the indeterminate monster Carol (voice of James Gandolfini) erupts into a rage and rips an arm off his bird-like friend Douglas (voice of Chris Cooper). There is no fountain of blood; sand trickles out of the stump. If that surprising, whitewashed act of violence — this is a movie based on a children’s book? — isn’t enough, one-armed Douglas spends the rest of his screentime with a twig pathetically jammed into the stump.

The scene is emblematic of a disturbing nonchalance that threads the film and renders the story more horrifying and sad than enchanting and redemptive. This mean streak is a by-product of Spike Jonze’s and Dave Eggers’ questionable extrapolation from the nine sentences that make up Maurice Sendak’s famous book, an extension that creates a backstory for Max and, in the process, magnifies the psychological stakes. No longer is Max merely a rambunctious child sent to his room for misbehaving and talking back to his mother — I’M GONNA EAT YOU UP! — he is a boy so starved for attention from a divorced, overworked mother (who clearly loves him) and a teenaged sister who has moved on to friends her own age that he resorts to unusually aggressive antics to get noticed.

Where the Violent Things Are

Not just aggressive, however. A wrestling match with the dog is rough enough to make the ASPCA, and any animal lover, squirm. A fort is designed with an (imaginary) feature that would automatically cut out the brains of unwelcome visitors. A dirt clod fight in which he encourages bullying of the weakest wild thing, a goat voiced to tender self-effacing effect by Paul Dano, with injury as the result. On it goes, defined by Max (Max Records) not simply talking back to his mother — warmly played by Catherine Keener — but biting her before running away from home. Whatever sympathy Max’s family situation might evoke is largely blunted by all this unpleasantly amplified anger. Unlike the Max from the book, it’s difficult to accept that a simple introspective dream can solve (if it solves anything) a major psychological sort of disturbance that only TV’s Supernanny or a child psychologist would willingly navigate. Naturally, this makes it equally difficult to accept the film as a general portrait of childhood.

The casual violence is not solely confined to Max. Jonze and Eggers, in conceiving the wild things, are depressingly cavalier. Wild thing KW (voiced of Lauren Ambrose), notably, throws stones at her friends Bob and Terry to get their attention, then carries them around like pets. It says something that even Max is skeptical. The environment is wantonly abused — one of the wild things punches large holes in trees for the fun of it, construction of the aforementioned fort involves massive (and largely unseen) forest destruction. All of it crowds out the possibility of wonderment at Max’s fantasy world despite the wonderful puppetry of the wild things and the idyllic beauty of the film’s Australian settings.

If the violence suggests a pathology beyond the story’s ability to handle, many of Jonze’s and Eggers’ choices in adapting Sendak’s story — and given the book’s skeletal text, calling the film an adaptation is generous — convey an artistic vision that doesn’t stand on solid ground. Max’s ascension to king of the wild things and self-rescue from being eaten doesn’t begin with a magnificent staring contest in which his willpower reigns supreme but with an elaborate series of lies and silly confabulations. Fortunately for Max, the wild things aren’t very bright — or, at least, they subscribe to the same child logic he operates by. His crazy, desperate imaginings save him and earn him the king’s crown, ominously taken from a pile of bones. The letter of the scene, however, takes away from its spirit; how much more powerful would Max’s first encounter with the wild things have been had it been wordless, all growls and yellow-eyed stares? Certainly Records, a bubbling cauldron of thoughts and emotions, has the ability to play it.

Where the Mopey Things Are

Equally troublesome are the wild things themselves, a sorry bunch of mopes not so much the embodiment of Max’s freedom from rules and consequences but allegorical surrogates for his real-world life. One would expect that the physical manifestation of Max’s various personas and emotions would mirror Max’s own evolving realizations. Yet as much as putting Max in a parental role vis-à-vis the wild things presents an ironic role reversal, Jones and Eggers are at a loss with how to squeeze the allegory from the literal. The wild things’ conflict with one another — easily solved when viewed with adult maturity, but understandably restricted in light of childhood irrationality — is left unresolved as Max follows the dictate of the plot that requires him to, eventually, return home. While Max ostensibly learns something, his understanding is not reflected in creatures supposed to reflect the contents of his psyche. The ending, then, taken straight from the book seems especially hollow and inauthentic given the magnitude of Max’s emotional troubles and the paltry lesson he may or may not have absorbed.

“Where the Wild Things Are” deserves admiration for Jonze’s visualization skills, even if the film could have benefited from less realism and more phantasmagoria. The wild things are not only gorgeous to look at but lovingly put into motion, as if Maurice Sendak’s illustrated wild things became living wild things, and Lance Accord’s cinematography is creamy without being overrich. Less successful, however, is the jagged score by Karen O (of the Yeah Yeah Yeahs) and Carter Burwell, which becomes grating with all the high-pitched children singers. Also admirable is the attempt, rooted in Sendak’s book, to get a grip on children’s emotional experiences both good and bad, even if the attempt is not truly a child’s experience but an adult interpretation of a child’s experience – as Jonze and Eggers intended. With neither feelings of elation when Max goes on a wild, carefree rumpus with the wild things, however, nor a sense of longing when that freedom comes with distance from the people who love us, Where the Wild Things Are is, to the end, a mirthless thing. Even Terry Gilliam’s almost-masterpiece Tideland, a gruesome film that involves considerably higher stakes than childhood loneliness, succeeds in using genuine, innocent astonishment to bring into focus the sorrow and despair of a troubled child. For all that the song goes “All is love,” the film alternately screams and whimpers that all is gloom.

Entertainment: zero stars

Craft: * (out of two)

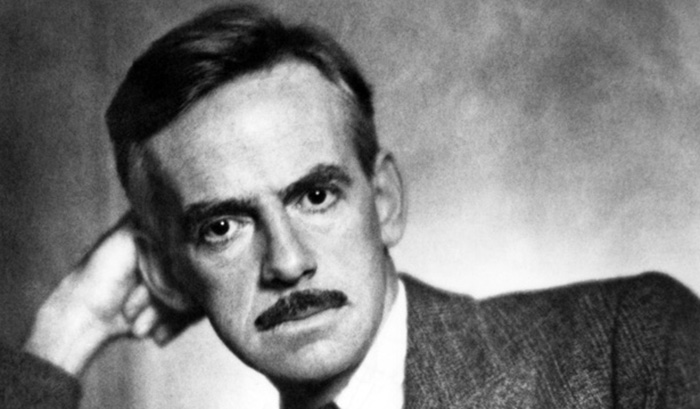

Directed by Spike Jonze. Written by Jonze and Dave Eggers, inspired by the book and illustrations by Maurice Sendak. Starring Max Records, Catherine Keener, and Mark Ruffalo. With the voices of James Gandolfini, Paul Dano, Catherine O'Hara, Forest Whitaker, Michael Berry Jr., Chris Cooper and Lauren Ambrose. 101 minutes. Rated PG (for mild thematic elements, some adventure action and brief language).

Frédérik invites you to discuss Where the Wild Things Are at his blog, www.inkandashes.net.