A review of “White Marriage” on stage at the Odyssey Theatre.

[img]2544|exact|||no_popup[/img]

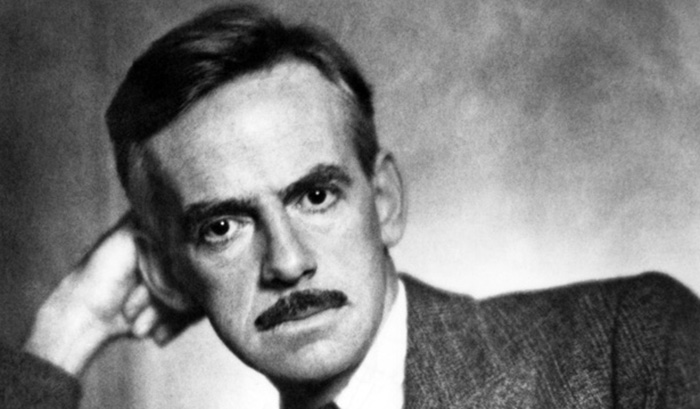

The French call it a mariage blanc, which translates to “white marriage,” although “blank marriage” would be equally appropriate. It’s an expression that refers to unconsummated nuptials. As the title of a play by noted Polish playwright and poet Tadeusz Różewicz, however, it takes on the unintended meaning of a play with unconsummated drama.

Ostensibly the story of a naïve girl, Bianca, growing into womanhood while confronted by her impending marriage to an equally naïve boy named Benjamin, Różewicz’s fantasia concerns sex. At the cusp of puberty, young Bianca is not so much innocent, but beholden to a slanted, idiosyncratic perspective of sex that Sigmund Freud, whose name should have been spelled with an “a” instead of an “e,” would have approved. Suspicion and terror – both influenced by an excess of imagination that is inflamed through a volatile relationship with her precocious best friend Pauline.

It might be easy to imagine a structured narrative from these preceding sentences, a slender path that navigates the play’s theatrical woods to deliver an insightful account of blossoming womanhood (in all the meanings implied by the botanical metaphor). Yet White Marriage is not so much structured as cobbled, stuffed as it is with unexamined ideas that sometimes approximate a plot milestone or thematic statement but, more often than not, merely perform a pirouette before ceding the stage to the next idea.

Thus we have Pauline as a sisterly best friend to the play’s erstwhile fulcrum, alternately teasing and loving as a close sibling might, but later adopting the persona of a malicious Lolita who capriciously takes advantage of an indirect opportunity to unravel Bianca. We have Bianca’s father established as a relentless philanderer, with Bianca’s mother as a woman whose hatred for him – since their wedding night! – leads her to reject sexual intimacy. The play teases lesbianism and gender identity dysfunction, but never forms anything substantive out of meager hints. Incestuous pederasty, however, is offered in full-force, first as dismissive comic relief then escalated into a sleazy scenario that is far from Vladimir Nabokov. “Nothing begets nothing” is put forth as Różewicz’s philosophy in Edward Hirsh’s foreword to the playwright/poet’s latest collection of poems, Sobbing Superpower. With all the fertile seeds for dramatic scenarios in play, White Marriage subverts the axiom and we have everything that begets nothing.

There are, certainly, dramatic incidents in that conceptual salad of sexual musings – that is, theatrical incidents that are very capably performed by a skilled cast. Yet the play is not sufficiently concrete to create drama, nor sufficiently surreal to invite the audience to forego drama and partake instead in dream logic with its phantasmagoria of interpretive ambiguity. Despite a reputation for the unconventional, the only conventions Różewicz breaks are the provisions of psychologically coherent characterizations and a purposeful narrative. Or perhaps it is the convention of writing a good play that is being defied, in which case White Marriage succeeds very well as a bad play.

Ron Sossi’s direction, which displays painfully conventional biases, reinforces the impression that this is a play about women put on by men. Why, for example, is a production about sex still indulging clichéd artistic direction when it comes to nudity? Neither the play nor Sossi make any demands of the men in terms of shedding clothes. But Sarah Lyddan and Yulia Moissenko, in non-speaking but nonetheless animated parts, are made to prance around with their blouses unbuttoned, while Emily Goss, who plays Pauline, is made to offer a full-frontal view of her chest while Kate Dalton caps the play with the full monty for a demeaning attempt at irony. The question is not the nudity itself, or even its distribution among cast members, but the sexist assumptions that often see women’s bodies paraded for either titillation or “dramatic effect,” while men hide in their clothes.

Another question: Why is it that when it comes time to dress the cast in animal masks, the pig face is given to the least slender member of the cast?

By all indications, this should be an outré production, yet the text and direction suggest cowardice. White Marriage asks no questions of sexuality. It takes no stance other than to offer the reductionist dichotomy that forms the play’s only discernible pattern: The ungovernable chaos of animal lust versus the frigid order of civilization. Here we have sex as a corrosive force that damages women and leaves men as nothing more than perpetually rutting creatures. The only certainty is cynicism, which comes into sharp focus during the second act when the first act’s comedy is abandoned in favour of an impending sense of doom. There is no exit in this play for the confused and damaged betrothed. They receive no help or guidance from their elders.

If this is avant-garde, then the avant-garde successfully has joined the ranks of the passé. Perhaps there was a jolt to be had in 1974 when Sossi first staged the play at the Odyssey. Today, however, the production is merely a bourgeois provocation that reinforces rather than unsettles societal conceptions of sexuality. It’s arguably bad critical form to ask why a play didn’t do this instead of that, but I can’t help asking: Why not undermine the opposition of sex and civilization? Why not celebrate sex as fun, or at least acknowledge the spectrum of attitudes towards it? Even the pornographer, however coarse, understands that eroticism must be rooted in a measure of carefree pleasure. That, too, would be provocative, to praise instead of condemn the pornographic. But no: we are given tiresome dread.

Perhaps there’s something in Poland’s water, but if it’s provocation you want, consider another Polish artist, filmmaker Walerian Borowczyk, who passed away in 2006 but was, at his peak, a contemporary of Różewicz. A critically-praised animator notable for short films such as Les Jeux des Anges (“Angel Games,” which was praised by Terry Gilliam as one of the 10 all-time best animated films), he achieved fame and acclaim for live-action art-house films such as Goto, Island of Love. However, when his work became more explicitly erotic – some would unfairly say pornographic – most notably with Contes Immoraux (“Immoral Tales”) and subsequently his justly infamous La Bête (“The Beast”), critics replaced his golden star with a tin one. Yet any one of the four vignettes that comprise Immoral Tales, an artsy anthology of the perversely erotic, surpasses White Marriage in impact. Take the second, Thérese, Philosophe. The titular girl talks with Christ, discovers the joys of self-sufficient pleasure, and is later disturbingly implied to be violated by a tramp. Ironically, a title card prior to the short informs us of her candidacy for sainthood on account of that violation. Contrast this with a parallel scene in White Marriage, in which Bianca relates to Pauline a “vision” that involves a nocturnal molestation by St. Nicholas and lots of red. Maybe there’s a menstrual allusion there, a fear of growing into womanhood, but the metaphorical agitation pales in comparison to Borowczyk’s: the theological unease, the space/time pleasure occupies outside of right and wrong, the motion to overturn the sexual conventions of religion and society.

While I don’t subscribe to the amorality in Borowczyk’s work, one of the less appealing trends among certain Surrealists, I admire his willingness to deliver transgression that is unafraid of eroticism and, crucially, forces audiences to take a stance, even if one of opposition. White Marriage provokes lengthy essays, but otherwise fades to black.

White Marriage. Written by Tadeusz Różewicz. Directed by Ron Sossi. On stage at the Odyssey Theatre until May 25, 2014. For information and tickets, call (310) 477-2055 ext. 2 or visit www.OdysseyTheatre.com.

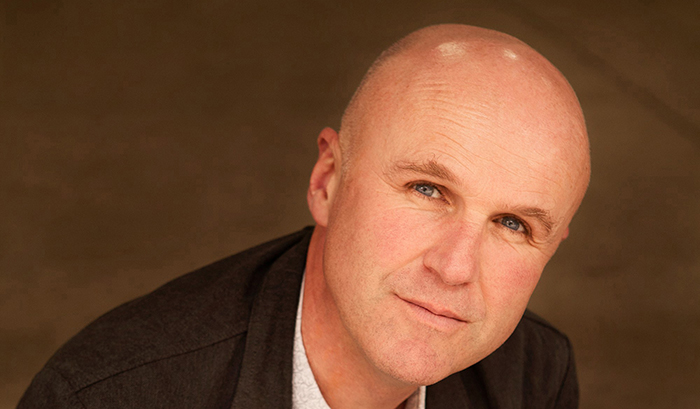

Frédérik Sisa is the Page's Assistant Editor and Resident Art Critic. He is also a tweeting luddite and occasional blogger, and can be reached at fsisa@thefrontpageonline.com.