Although Tadhg Murphy offers as fine a performance as one could ask for, it’s telling that the titular character in The Cripple of Inishmaan is played by an able-bodied performer. The lazy interpretation of this would invoke political correctness, but it would be more nuanced to contextualize it within the play’s general movement to keep disability at a distance. Hence, Irish playwright Martin McDonagh gives us the elements of a sitcom; a rural Irish island, a cast of idiosyncratic characters, and in the middle of it all, a deformed lad named Billy who is constantly referred to as “Cripple” Billy just in case his disability isn’t obvious enough to him. The nicknaming, even from what passes as family for Billy, is the sort of casual, reflexive cruelty that highlights a pervasive lack of empathy towards that which, in any context, constitutes “the other.” But there is outright hostility and contempt towards Billy’s condition as well, most obviously from Claire Dunne’s masterfully violent and spiteful Slippy Helen, although her venom is just as easily dispensed towards everyone around her.

[img]1148|left|||no_popup[/img]

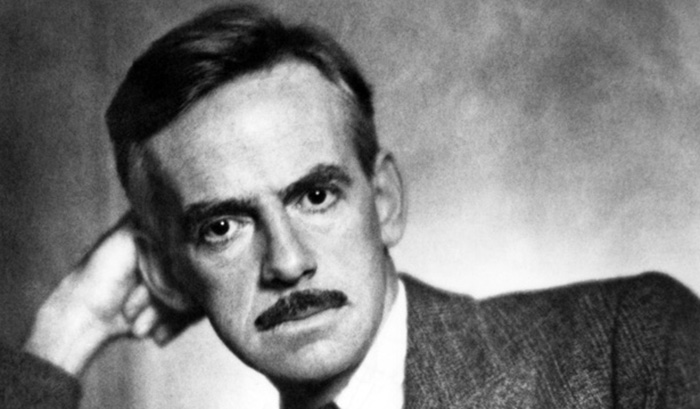

Tadhg Murphy, left, and Dearbhla Molly, at the Kirk Douglas

None of the usual mistrust and loathing on display constitutes an honest engagement with disability, however, particularly given how the play couches it in humour. McDonagh is a very funny and literate man, darkly so, and he has the gift of plucking unlikely laughs from quirks that are oftentimes more despicable than charming. If the play’s measure could be taken solely from its capacity to provide well-written dialogue and to provoke laughter, it would be an unqualified success. Yet by the time the second act is underway, the humour becomes more obviously a barrier to the subject rather than a bridge, like laughing at a funeral to keep yourself from realizing you never much liked the deceased anyway.

To the residents of Inishmaan, then, Billy is an object of ridicule, but the play works to insulate the implications of this by turning Billy into something just as disingenuous for the audience: an object of pity. While the characters make much fuss over Billy’s condition, the playwright himself joins in the condescension as he provides complications that don’t arise from his characters’ actions but from his own artistic choice. The scenario feels manipulated, in other words, and with that manipulation comes a loss of authenticity and insight.

A general lack of events doesn’t help the impression that The Cripple of Inishmaan lacks focus. Characters are essentially dragged from vignette to vignette – in the seemingly endless Act 2, the audience gets dragged along too – that amount to conversations in different locations. Other than the off-screen arrival of an American film crew in search of some Irish for their films and a few plot points arising from this, nothing actually happens to pick up the characters, shake them, and hold them to the light to see how they change. There’s nothing wrong, of course, with a talky, barely eventful piece — provided the characters have the complexity to withstand the added scrutiny. As McDonagh’s characters suffer from a lack of introspection, the talking, however funny, is just that – talk.

What passes for complexity rests on a gimmick that didn’t work when Paul Haggis tried it in his racially-charged film, Crash, and certainly fails to persuade in McDonagh’s hands (although McDonagh’s play precedes the film by a good many years). Said gimmick: Upending audience expectations by suddenly flicking characters from their better angels to devils or vice-versa. Illustrating the full gamut of human benevolence and malice requires gradients, however, not the action of light switches. By the play’s end, the reversals don’t amount to much either because they have no real foundation, and thus lack credibility, or they simply confirm what we’ve known all along: the play’s characters are merely brutish and, when well-intentioned, vulgar. Consider Babbybobby, a seaman presented with the veneer of a soft heart but whose glee at throwing bricks at cows and rocks at people’s heads precedes a later act of violence that would shock if it hadn’t been telegraphed. The problem is that, tucked away in the psychological as well as physical violence the characters are willing to inflict on one another are glib rationalizations that have all the weight of a one-panel comic book origin story. Oh, look, this one tragically lost his wife to tuberculosis. And over here, this girl has been abused by priests. Strewn about in a play whose characters play fast and loose with the truth, these small revelations have no real drama. If the unexamined life is not worth living, then unexamined characters are hardly worth getting to know.

But the production, directed by Garry Hynes, is skillful and well tuned, with Nancy E. Carroll the standout in the cast as the drunkard mother of Inishmaan’s local gossipmonger. The play is disturbingly funny; there is that. What a shame that the bleak hilarity is allowed to obscure and forgive a lack of genuine sympathy or understanding for what it means to be disabled.

“The Cripple of Inishmaan,” by Martin McDonagh. A Druid and Atlantic Theater Production. Directed by Garry Hynes. Starring Dearbhla Molloy, Ingrid Craigie, Dermot Crowley, Tadhg Murphy, Laurence Kinlan, Clare Dunne, Liam Carney, Paul Vincent O’Connor and Nancy E. Carroll. On stage at the Kirk Douglas Theatre through Sunday, May 1. www.centertheatregroup.org

Assistant Editor: THE FRONT PAGE ONLINE

————————–———————-

web: www.thefrontpageonline.com

email: fsisa@thefrontpageonline.com

blog: www.inkandashes.net

…and also fashion with TFPO's The Fashionoclast at www.fashionoclast.com