On Friday, “41st & Central: The Untold Story of the L.A. Black Panthers” will open for a limited engagement as part of the Pan African Film & Arts Festival’s Encore Program at the Culver Plaza Theatres in Los Angeles.

Bernie Carter, 76, the oldest of 10 siblings that included Alprentice (Bunchy) Carter, former leader of the Southern California Chapter of the Black Panther Party for Self-Defense, who was murdered at UCLA’s Campbell Hall in 1969, recently viewed the film at a private screening for the first time.

A retired engineer, Mr. Carter, who now lives in Carson, is the first member of the Carter family to watch the film that features first-hand accounts as told by the original surviving Black Panther members of Bunchy Carter and John Huggins’ murders.

“Powerful, dynamic — the film rekindled a lot of old emotions,” explains Mr. Carter. “I remember my brother sitting me down and explaining to me who this group called the Black Panthers were.

“After our mother and our stepfather split up, and with me being the oldest brother, my mother looked to me for support in guiding my younger brothers. I was expected to lead by example. I remember thinking that the Panthers were just another gang he was involved in. I worried about the effect it was going to have on our mother.”

[img]819|left|||no_popup[/img]

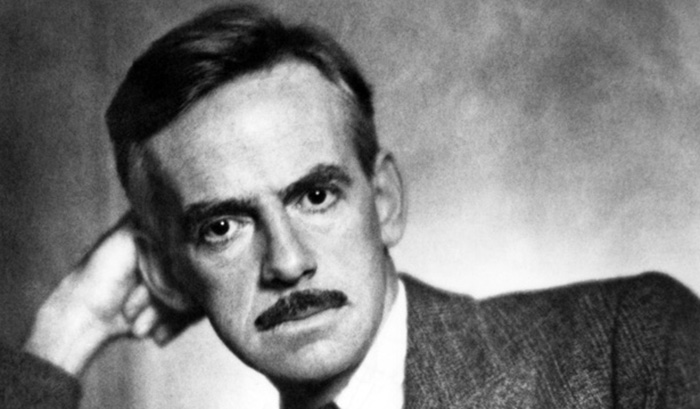

Bernie Carter, 73, at left, with filmmaker Gregory Everett

Family History

Prior to joining the Black Panthers, Bunchy Carter, a graduate of Freemont High School was the leader of the Slauson Renegades, a local Los Angeles gang. After graduating high school, Bunchy began working for an upscale department store in downtown Los Angeles on Wilshire.

Laughing, he recalls,” I remember my first introduction to the Nation of Islam was when Bunchy and our brothers, John and Glen, came into the house one day and declared ‘no more pork!’

“It drove my mother insane. Here she was trying to feed a family of 10 on a limited budget where there was no room to be selective about what was for dinner. It was utter chaos.”

“Bunchy was a partygoer, a ladies man, what young people now call a player,” remembers Mr. Carter.

“In 1961, Bunchy wanted a car. One day he came to me and asked me if I would co-sign on a car for him. We looked for a car for a couple weeks. Finally, we settled on a 1956 red and black MG. At the time, he was just enjoying living life. When he got that car, you couldn’t touch Bunchy with a 10-foot pole,” he chuckles.

“Sometime after that, Bunchy was sent to Soledad Prison for attempting to rob a Security Pacific Bank. He was there for four years. He came out two years after the Watts Riots ended and there were all these programs being started. Our mother was involved with a program call N.A.P., and they had teen posts. She got Bunchy involved in one of the teen posts at Central and Nadeau. That’s where Bunchy met Caffee Greene and Nate Holden because they were also involved with those programs. At the time, they were working with Supervisor Hahn.

“From that, all of a sudden, all I know is he’s in this organization called the Black Panthers. He begins traveling back and forth up north. He had formed a kinship with Bobby [Seal], David [Hilliard], and Eldridge [Cleaver]. Initially, I thought it was just another gang.”

All of These Years Later

Mr. Carter explains that their mother, Nola Carter, now 93, was feeling anguish. She worried about Bunchy’s well-being, and also that, being the older brother, it was up to Mr. Carter to find out exactly what was going on and what this group called the Panthers was all about.

“Bunchy sat me down. He explained his reasons for joining the Black Panthers,” he continues. “He said he was tired of being oppressed.

“You have to understand that Bunchy, he didn’t have the same fear I had. He was a very proud, strong young man.

“By this time, he had been arrested and incarcerated, whereas a person like me, who had not been involved in any of that kind of stuff, was scared.

“There were certain values that our mother instilled in me as the oldest brother. Like Bunchy, I had a role to play in our family, and he had his. The bottom line was that I knew something bad was going to happen. I knew my brother felt strongly about the injustices that were happening to black people at the time. But it was his destiny to fulfill, and I was concerned with making sure it had as small an impact as possible on our mother.”

No Closure

In March of 1968, Arthur (Glen) Morris, brother of Bernie and Bunchy Carter, Bunchy’s first bodyguard, was shot and killed on 111th, between Normandie and Vermont avenues. He was the first member of the Black Panther Party to be killed.

“When Glen died, things really started to changed,” Mr. Carter explains. “Almost a year after Glen’s death, Bunchy and John [Huggins] were murdered at UCLA.”

A murder that still is unsolved today.

Mr. Carter says that he had heard about the documentary film being done about his brother’s death, a film that took six years to bring to completion.

After repeated attempts to get him to see the film by his friend J. Daniel (Skip) Johnson, who was standing steps away from Huggins and Carter when they were gunned down, he showed up, unannounced, at a press screening for the film.

Mr. Johnson, a 21-year-old UCLA senior majoring in political science in 1969, who had chaired the meeting where the murders occurred, had been interviewed for the documentary “41st & Central: The Untold Story of the L.A. Black Panthers.”

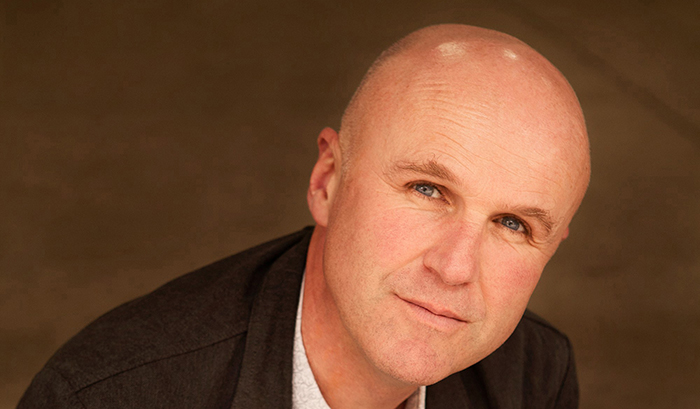

He wanted his friend Bernie to see it. In a theatre full of journalists who had no idea until that time that a member of the Carter family was in the room, he stood up, moved to tears, and praised the filmmaker Gregory Everett.

He says now on the eve of the film’s Los Angeles limited engagement at the Culver Plaza Theatre — for seven days, tomorrow through next Thursday —that while he praises the film for its accuracy in telling his brother’s story, he’s not sure that at 93, his mother could handle revisiting the lost memory of not only one but two sons during the Black Panther Movement.

But he encourages the community to come out and see the film.

Throughout the film’s engagement at the Culver Plaza Theatre, members of the Carter family are expected to attend.

But Mr. Carter is unsure about his mother.

“41st & Central: The Untold Story of the L.A. Black Panthers” features new and exclusive interviews from Black Panther party leaders Geronimo Ji Jagga, Elaine Brown, and Kathleen Cleaver, Los Angeles City Councilmember and former LAPD police chief Bernard Parks.

The film is the first part in a documentary series that follows the Southern California Chapter of the Black Panther Party for Self Defense from its glorious Black Power beginnings through to its tragic demise,

It explores the Black Panther ethos, its conflict with the LAPD and the US Organization, as well as the events that shaped the complicated and often contradictory legacy of the L.A. chapter.

Using exclusive interviews with former Black Panther Party members along with archival footage detailing the history of racism in Los Angeles, including the Watts Uprising.

“ 41st & Central: The Untold Story of the L.A. Black Panthers” is being called the most in-depth study ever of the L.A. Chapter founder Alprentice (Bunchy) Carter. The film features first-hand accounts by the surviving original members and gives the viewer an eyewitness account of the Bunchy Carter and John Huggins murders at UCLA in 1968.

Also featured in the film are former Black Panther members Ericka Huggins, Roland and Ronald Freeman, Wayne Pharr, Jeffrey Everett, Long John Washington, US Organization member Wesley Kabaila and UCLA Prof. Scot Brown among others.

Produced and directed by Gregory Everett, son of L.A. Black Panther Jeffrey Everett, and co-produced by Roland Freeman, “41st & Central: The Untold Story of the L.A. Black Panthers” will screen four times a day at 9919 Washington Blvd. Tickets are $10 and are on sale now at www.paff.org and www.41central.com.