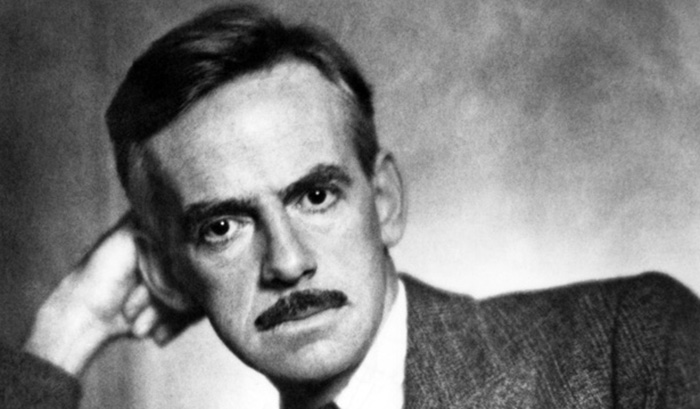

[img]645|left|From left, Ross Hawkins, Budd Schulberg, Ben Stiller and John Jordan of West Los Angeles College ||no_popup[/img]Writer, producer, director Budd Schulberg, winner of the second Thomas Ince Award at the Culver City Backlot Film Festival in February of 2007, died at his home in Westhampton, N.Y., on Aug. 5, at he age of 95.

I was able to get Schulberg to attend the Backlot Film Festival in 2007 thanks to the intercession of Scott Eyman, author and book editor for the Palm Beach Post.

Eyman had written a wonderful book on John Ford, called “Print the Legend,” and was now writing a book on Louis B. Mayer titled “Lion of Hollywood.”

A lot of information about Mayer's early years in Hollywood was supplied to Eyman by Budd Schulberg.

Schulberg's father, Benjamin Percival Schulberg, was born in Bridgeport, Conn., in 1892. He worked in the fledgling film industry in New York City until 1919 when he moved to Hollywood where he operated “Preferred Pictures.”

He is credited with discovering Clara Bow.

He and L.B. Mayer became partners in a small studio in Edendale, the Mayer-Schulberg Studio.

Hiding His Intentions

Mayer kept the elder Schulberg in the dark about his negotiations to head up the new film company being formed by Marcus Loew that would take over the struggling studio in Culver City run by Samuel Goldwyn.

In 1924, Mayer became head of what became Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer.

Schulberg was left holding the bag for the rent on their joint venture.

According to Budd, his father told him, “When I die and after I'm cremated, I want you to take my ashes over to (Mayer's) office. Blow 'em in that SOB’s face.

B.P.Schulberg went on to join forces with Adolph Zukor, and he later became head of Paramount Pictures. The elder Schulberg was ousted from Paramount in 1937.

He was out of the business until 1940 when he went to Columbia where he produced six pictures in three years. Schulberg retired in 1943. He lived another 14 years, dying at his Florida home in Key Biscayne in 1957

When we made the decision to nominate Budd Schulberg for the second Thomas Ince Award at the Backlot Film Festival, I recalled a conversation with my mother back in 1959.

I was sitting in the kitchen reading an article in Time magazine about how the legendary Garden of Allah Hotel in Hollywood had been torn down and replaced with a parking structure.

Early Memory

My mother paused from fixing dinner to reflect for a moment. Unknown to my brother and me, she had worked briefly at that famous hotel and watering hole where the likes of Errol Flynn, Humphery Bogart, Greta Garbo, the Marx Brothers and W.C. Fields hung out.

She recalled meeting a “nice young writer” there who was working with F. Scott Fitzgerald and trying to keep him reasonably sober. The writer was Budd Schulberg, then collaborating with Fitzgerald on a light comedy set at Dartmouth College, called “Winter Carnival.”

Schulberg had attended Dartmouth before returning to Hollywood to work as a screenwriter.

Both Schulberg and Fitzgerald were fired from the Walter Wanger-produced film. They were replaced by Lester Cole, one of the founders of the Screen Writers Guild, who

later was blacklisted by the HUAC for being a member of the Communist Party.

When I first spoke to Schulberg, I told him my mother remembered him from the Garden of Allah.

He grew silent for a moment. “I have a lot of memories of that place,” he said softly.

The Garden of Allah was converted from a mansion at the corner of Sunset Boulevard and Crescent Heights into a hotel with bungalows and a swimming pool by the silent film actress Alla Nazimova. On the advice of her business manager, Nazimova

launched the project to provide revenue for her retirement.

However, by the time the hotel was completed, she was bankrupt and had to sell the property. Nazimova eventually was reduced to renting a flat in a small corner of her former home.

It Won’t Go Away

The Garden of Allah was home to, among others, Robert Benchley, Fitzgerald and Shelia Graham, who wrote a colorful book about the hotel in 1970 published by Crown.

In June of 1959, The Garden of Allah was torn down. Today it is a pink strip mall with fast food restaurants and a pizza parlor.

The lyrics “They tore down the Pink Cadillac and put up a parking lot…” were said to have been inspired by the destruction of The Garden of

Allah.

In 1993, the singer Don Henley recorded “The Garden of Allah,” a lament about the changes that have taken place in Southern California, as in “Things are gonna get mighty rough here in Gomorra by the sea.”

Budd Schulberg was educated at Los Angeles High School where he edited the school newspaper. After studies at Deerfield Academy, he entered Dartmouth College, earning his A.B. in 1936.

Back in Hollywood, he began to write and publish short stories, and became a member of the Communist Party.

In 1941, Schulberg wrote his best-selling novel, “What Makes Sammy Run?” about a Jewish boy born in New York's Lower East Side and escapes the ghetto by rising from newspaper copy boy to successful screen writer to top Hollywood producer.

Sammy Glick is totally unscrupulous. He rises to the top of the heap by backstabbing others. He observes at one point, “Films come in cans. We’re in the canning business.”

“What Makes Sammy Run?” created a stir in Hollywood. In Arthur Marx's biography of Samuel Goldwyn, he states that Goldwyn offered Schulberg money not to have the book published because he felt it was perpetuating an anti-Semitic stereotype by

making Sammy Glick such a heel.

L.B. Mayer was even more outraged. He suggested to Schulberg's father that Budd should be deported. “Where are you gonna deport him to, Catalina?” asked the senior Schulberg reminding Mayer that Budd was born in the U.S.

Schulberg told me that he left the Communist Party while writing “What Makes Sammy Run” because Lester Cole and other members of the party tried to get him to color the novel with Communist propaganda that he felt was inappropriate.

Two years ago, Schulberg arrived for the Backlot Film Festival two days before the event, accompanied by his wife Betsy. He was interviewed at length by author and film critic Leonard Maltin on Tuesday, Jan. 30.

The next night, he was given the Thomas Ince Award at the historic Veterans Memorial Building in Culver City. On hand to present him with the Thomas Ince award was actor-director Ben Stiller who had been slated to appear in the Warner Bros. Production of “What Makes Sammy Run?” Also on hand for the presentation was Daniel Selznick,winner of the first Thomas ince Award.

Saturday, Feb. 3, Budd was to appear at a rare screening of “Wind Across

the Everglades,” a film that Schulberg produced in 1958, starring Christopher

Plummer and Burl Ives. It was the story of a turn of the century game warden

in Florida and his struggles against big time poachers.

Two weeks before the film was scheduled to finish, Schulberg fired director Nicholas Ray and completed directing it himself.

Schulberg called me and said he was too tired to attend the screening, and so he invited me to his suite at the historic Beverly Hills Hotel.

When I arrived, he was closing out an interview with William Estrada, the curator of the History Department at the Los Angeles Natural History Museum.

In our last meeting before he went back to New York, Schulberg told me of his experiences during World War II. While serving in the Navy, he was assigned to the Office of Stratigic Services (OSS), working with John Ford's documentary unit. He rewrote the narration for Ford's Academy Award-winning documentary, “December 7.”

Later, Schulberg assisted in rewrites of Ford's classic World War II epic,

“They Were Expendable,” starring John Wayne and Donna Reed. During our talk, Schulberg recounted his experiences with Ford.

“I was always kept off guard by Ford,” he recalled. “The first time I went to see him at his office, he demanded full military decorum, including a proper salute. He was an Admiral and I was a Junior Officer.

“The next time I went to see him, I saluted. He looked back at me and said, 'Oh, for Pete's sake, Budd. We don't need that. Sit down.”

Following V.E. Day, Schulberg and director George Stevens were among the first American servicemen to liberate the Nazi-run concentration camps. They were involved

in gathering evidence against war criminals for the Nuremberg Trials. He told me about arresting documentary filmmaker Leni Reifenstahl at her chalet in Austria to identify the faces of Nazi war criminals in German film footage they had obtained

from a German film editor.

In 1950, Schulberg published what I felt was his finest novel, “The Disenchanted,” about a young screenwriter who collaborates with a famous novelist on a screenplay

about a college winter festival. The novelist was a thinly disguised F. Scott

Fitzgerald and Schulberg was the young Jewish screenwriter assigned to work with him.

“The Disenchanted” was the 10th best selling novel in the United States in 1950. It was adapted as a play in 1956, starring Jason Robards Jr., who won a Tony Award for his performance as the novelist.

Schulberg testified as a friendly witness for the House Un-American Activities Committee. He told them that he had left the Communist Party in 1941 when members had tried to influence the content of “What Makes Sammy Run?”

Schulberg won the Academy Award for his screenplay, “On the Waterfront,” which was based on a series of articles he had written for the liberal Catholic magazine, Commonweal. Karl Malden's role as the tough Irish priest who defies the mob was based on real life Father John Corridan who attempted to reform the corrupt Longshoremen's Union. Lee J. Cobb's waterfront mobster “Johnny Friendly” was

modeled after Albert Anastasia.

Schulberg told me the original title for the film was “Bottom of the River,” but it was rejected by every studio in town. Marlon Brando originally turned down the role of Terry Malloy because he didn't want to work with director Elia Kazan who had testified as a friendly witness for the HUAC. When Brando finally accepted the role,

Columbia Pictures agreed to distribute the film. Frank Sinatra, fresh from his

Academy Award-winning role in “From Here to Eternity,” thought he had the role of Terry Malloy. He sued producer Sam Spiegel for breach of contract.

Humphery Bogart's last film, “The Harder They Fall” (1956) — about a down and out sportswriter hired by a shady fight promoter to publicize his latest find, an unknown

boxer from Argentina, reportedly was modeled after heavyweight boxer

Primo Carnera — was based on Schulberg's novel of the same title.

Schulberg also produced “A Face In The Crowd” in 1957, reuniting with director

Elia Kazan. The film was based on a short story about an Arkansas hobo who becomes an overnight media sensation and then self destructs when he becomes drunk with power.

The film starred Andy Griffith in a role unlike any other he has been seen in.

Patricia Neal and a very young Lee Remick co-starred.

Schulberg, for a time, was a sports- writer and chief boxing correspondent for Sports Illustrated magazine.

When we concluded our interview that Saturday, Budd gave me a hard cover copy of his new book “Ringside — A Treasury of Boxing Reportage.” He signed it “For Ross Hawkins, For the honor you have bestowed on me at the Backlot Film Festival — Budd Schulberg.”

Mr. Hawkins may be contacted at rjhculvercity@aol.com