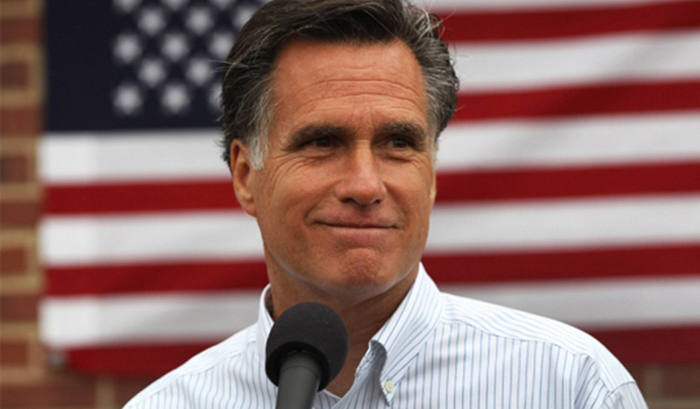

[img]1|left|Ari Noonan||no_popup[/img]In the opening rounds of the Bennett-Harris family’s civil suit against the California National Guard in the murder of their sibling, playing out in a Downtown courtroom, even an objective observer can be shocked by the inertia that froze the Culver City Police Dept. and the Guard four years ago last summer.

Both knew a killing was coming or threatened.

Their response: To stuff their hands deep into their pockets and look to the clouds.

Their lone exercise, it seems, was to shrug.

And now the family is reportedly hoping to win a settlement of between $5 million and $10 million in a wrongful death cause.

Until the last 24 hours of victim JoAnn Crystal Harris’s brief, sad 29-year-old life, neither the cops nor the Guard knew her name.

Or tried to learn her name, evidently.

Could or Should They Have Acted?

According to testimony, both agencies were fed an irresistible amount of evidence that Sgt. Scott Ansman intended to murder a woman he had met randomly and believed he had impregnated.

That was an inconvenient problem for the married Mr. Ansman. At the same moment in June 2007 when he learned Ms. Harris, a putative Guard recruit, was with child, his wife was delivering their third child.

That irony aside, Sgt. Erik Hein, who worked alongside Mr. Ansman every day at the Culver City National Guard Armory, noticed he was growing increasingly “unhinged.” That term has bobbed up repeatedly.

Sgt. Hein saw the desperate Mr. Ansman, now doing life without parole, searching the internet for a way to induce an abortion. Failing that, Mr. Ansman openly inquired about paying a dupe to kick or punch Ms. Harris to end her pregnancy. Later, we are told the foiled, frustrated Mr. Ansman, who had little money and was working two jobs, asked pals to find a hit man.

After six weeks of this bizarre daily behavior, the exasperated Sgt. Hein went to the cops.

A contingent of three Guardsmen and a driver went to the police station 20 minutes after midnight on a Saturday night three weeks before the ghastly murder. Sgt. Hein, we are told, related the ugly details to Det. Jay Garocochea.

Huddling at such a peculiar hour when, I believe, the detective was off-duty, should have struck a chord with someone in authority.

Normal or Abnormal?

If Sgt. Hein and Mr. Ansman had been toiling in a standard workplace, surely the future killer’s antics would have attracted a superior’s attention. But the impression left in the courtroom was that the two men largely had the joint to themselves, meaning some standards of normalcy were suspended.

The National Guard traditionally has presented itself as a laissez faire institution — not quite traditional soldiers but still more militarily-oriented than you are or I am.

Laxity seems to have been rampant — not only at the Guard but in the Police Dept. The only detectable pseudo-discipline applied to Mr. Ansman was for the Guard to dispatch him to Guard quarters in Los Alamitos, Orange County, to practice war games.

After a couple weeks, he was brought back to Culver City, we are told, because Sgt. Hein thought it would be better for him to keep a direct eye on the killer-in-training.

Guard executives will dispute an assertion that they ignored shouting warning signs that Mr. Ansman was acting crazily and planning to dispose of Ms. Harris, which he did at the Armory on the tragic afternoon of Aug. 24, 2007.

While the cops and the Guard seem to have walked away from warning signs, the crazed Mr. Ansman only missed one bet: Failing to take out a full-page newspaper advertisement declaring, “Hello, I Am Going to Kill.”

We may have a better understanding by the end of next week when the civil suit is expected to conclude.